-

Author

Kim Paton and Zoe Black -

Date

9 Nov 2021

Essay

Toro Whakaara: An Introduction

Responses to our built environment

At the time of writing, after some months of relative normality, Aotearoa finds itself in lockdown again, a late and unwanted gift of Covid-19.

The strict conditions of Level 4 – no commerce except of the supermarket, petrol station and chemist variety; no workplaces or public facilities open; no recreation in public spaces – creates a unique moment of reflection to consider this exhibition. Ten practitioners – architects, urban planners, designers, artists and makers – were commissioned to think through the ways in which the design and use of the built environment impacts on a diversity of human experience.

The development of the exhibition originated with the term ‘hostile architecture’, also known as defensive architecture or unpleasant design. Think skateboard spikes on civic infrastructure, a park bench designed to deter people from lying down, or orchestral music pumped into a train station to discourage young people to loiter. It describes design strategies in urban spaces deployed to maintain order or control behaviour. Its technical definition was a useful starting point, but more broadly we wanted to consider how our cities and spaces are shaped, and whose access and use are prioritised through their design. To contemplate the power and politics of place through the social interactions, occupation and movement it allows.

With the challenges of Covid-19, a new assortment of containment, delaying and monitoring strategies that seek to control our movements and how close we can get to one another has become commonplace. Interventions to the city street-front and shop door, alongside new makeshift architectures like drive-through testing stations, have become urban design prototypes, tested and modified in real time as we are instructed where to go, how to queue, and when to touch. Here, the success of these new obstructions is in their visibility. The city and our shared public spaces are momentarily revealed to us anew, as the usual priorities of trade, recreation and transit fall away with the demands of a once-in-a-lifetime public health emergency.

We began bringing Toro Whakaara together by inviting the participating practitioners to a wānanga at Objectspace. This was a time for everyone to share their respective practices and collectively tease out the exhibition kaupapa. For some, ‘hostile architecture’ was a new idea and thoughts varied considerably in how to approach and interpret the term.

From the outset we stressed our desire for the exhibition to maintain a connection to the real world, to sites that the practitioners lived in, knew personally or were invested in. Our aim was to resist responses that became too abstracted. We weren’t here to solve big speculative problems – instead, we wanted the opportunity to see Aotearoa differently, the way these practitioners did. Each approached this provocation distinctively, and together encompassed a multiplicity of ways in which sites – the interior domestic space, the expansive moana, the sidewalk, the city – could be defined.

For many of the practitioners, hostility within the environments they live in is an everyday and traumatic consideration. Ngahuia Harrison emphasised how relationships between tangata whenua and the Crown have been continuously hostile, pointing to current legislation built on narrow and restrictive understandings the Crown has of how Māori relate to the moana and coastline and the impact this has had on the people of Ngātiwai. ĀKAU spoke about the vocal backlash they experienced when their first Te Reo Māori on the Streets mural was completed in Kaikohe.Where the majority of the hapori loved the transformation of the main street, a small section of the community was offended by seeing a celebration of te reo Māori on the main street of a town whose population is 80 per cent Māori.

Some practitioners talked to the power dynamics in our built environment that intentionally marginalise groups of the community. Raphaela Rose’s deep research into public restrooms reveals longstanding gender inequities that have shaped the accessibility and use of the city. The first facilities for women weren’t built until 1910, fifty years after a public male restroom was available in central Auckland. One year later, in 1911, Auckland Town Hall was opened without any women’s facilities included in its design.

Others spoke about the edges between public and private spaces, and the ways we navigate these thresholds, creating moments of celebration and advocacy for communities. Edith Amituanai’s respect for her neighbourhood sees her document the ways its in-between spaces are co-opted and put to use by inhabitants. Subverting overbearing placemaking design, her images capture ‘what we do, in spite of what they have done’.

Through the wānanga we saw how strongly culture and identity are tied to our experiences of place. Knowing a place is the only way you can really see it.

As an approach to the planning of public spaces, placemaking emerged in the 1960s as a design strategy that sought to enhance the human experience of a site by harnessing its attributes (land, architecture and patterns of use), alongside the active collaboration and participation of local communities. Its intent was to create active social spaces that citizens feel invested to care for and maintain. Over time its usage has drifted from grassroots associations to the word-speak of commercial property development and local government planning. In these settings true collaboration can be obfuscated and replaced with generic consultation processes, undermining the role of local citizens to freely engage and determine their own outcomes.

The projects in Toro Whakaara span an expansive range of sites and varied instances of community collaboration. From the deep waters of the Manukau Harbour to a corner fish and chip shop in Ōtautahi, the diversity in their selection reflects much of what contemporary notions of ‘placemaking’ might fail to capture. The geographies of place that contribute to individual and community identities are vast and non-conforming. HOOPLA, a social enterprise producing urban research by Nina Patel and Kathy Waghorn, extend their longstanding research into the Avondale Sunday Market. Located at the Avondale Racecourse, close to Tāmaki’s inner city, the view from the road is a no-frills flurry of people and the large trucks of market gardeners who’ve made the early-morning trip to clear stock by midday. Patel and Waghorn, both residents of Avondale’s surrounding area, are undertaking an unorthodox stock-take, seeking to assess and understand the movement of people, goods and services from a wide range of perspectives – trade, traffic, food waste, well-being and income generation. Sitting on an enviable portion of undeveloped land, the site of the market is increasingly under pressure. How do we measure the market’s contribution as a rich and productive suburban and neighbourhood hub, an endeavour that has been allowed to independently and on its own terms develop and thrive, against the accumulating pressures of ongoing housing shortages?

Textiles artist Kirsty Lillico works in floor plans and foraged carpet. Large swathes of carpet are sliced to scale off real-world architectural floor plans – modernist buildings, social housing and new apartment living all feature. The soft layers cut and slouch into unlikely wall hangings. For Toro Whakaara Lillico, a long-time resident of Pōneke Wellington, has focused on the city’s Gordon Wilson Memorial Flats. Opened in 1959 as public housing, the relative high-rise provided homes for innumerable people in need. In 2012 it was swiftly vacated in the face of frightening failures in the building’s structural integrity. Today the apartment complex sits uninhabited, an empty monument to its own architectural style, beloved by some for its design and derided by others as a failure of a city to adequately house its citizens.

Across the exhibition the impact of who (or what authority) maintains governance of a geography can be powerfully seen. It is vital that those making policy and public design decisions be required to consider the mauri and whakapapa of a place, and to have empathy for those impacted by decision-making, in order to create space for the expression of different knowledge systems and values.

A personal relationship to ‘architecture’ is out of reach for many – something that might only come into our vocabulary through television shows like Grand Designs or aspirational posts on social media. Here, the practitioners have each offered a way to rethink how we can regard architecture within the context of our everyday experience and its necessity to be responsive to the people who will use it.

When we approached ĀKAU to be part of Toro Whakaara, they agreed with the caveat that their involvement must include tamariki voices in the gallery and a real-world project. In keeping with their kaupapa of working with and for communties, in the coming months ĀKAU will be facilitating a Te Reo Māori on the Streets mural in Ōtautahi in collaboration with mana whenua and local kura. ĀKAU’s integrated doing and sharing of knowledge through the exhibition framework has been fundamental in shaping our understanding of what true collaborative and reflective design can look like. Their way of working will continue to influence the way we approach exhibition- making, stressing the importance of interlacing approaches that expand and extend back into the the real world.

As the exhibition came together, each project found its own shape and purpose. The title Toro Whakaara references tensions that exist between human experience and the built environment. The kupu ‘toro’ means ‘to explore’ and also ‘to reach’, while ‘whakaara’ can mean ‘hostile’ or ‘awaken’. The name was gifted to the exhibition by ĀKAU. We have appreciated the process of wānanga and collaboration that all the practitioners have been open to as we have developed Toro Whakaara. Through the integrity with which they have approached this process we are offered a lens to view their papakāinga, their cities and the places they hold connection with.

This text is republished from Toro Whakaara: Responses to our built environment, a publication produced by Objectspace to accompany an exhibition of the same name. The publication is edited by Tessa Forde, and copy-edited by Anna Hodge.

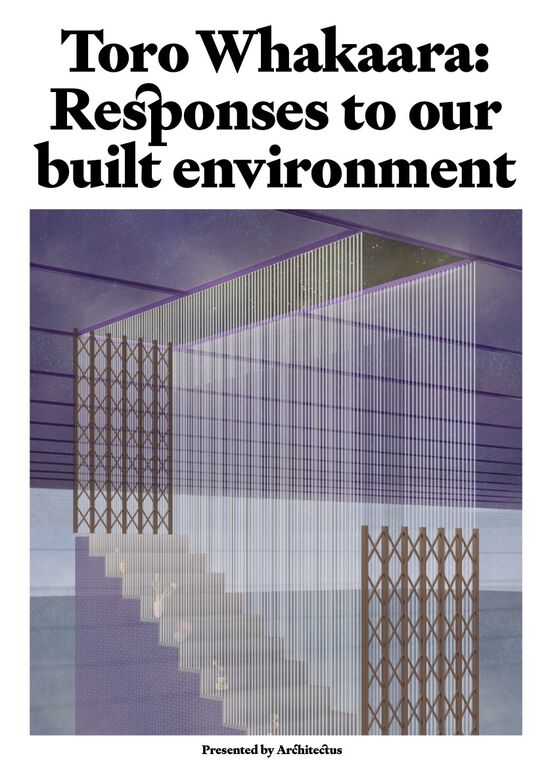

Publication front cover featuring Rapheala Rose, Wellesley Street East Convenience – steps to the depths in a haze of ultra violet purple, 2021. Design by Alt Group.