-

Author

Richard Fahey -

Date

25 Nov 2020

Essay

Tender Brick: The Material Epiphanies of Peter Hawkesby

The exhibition Tender Brick tracks the range and depth of Peter Hawkesby’s production since his return to full-time making in 2016. Peter Hawkesby was born in Cockle Bay, Auckland, in 1950, a time when street gutters were gouged from raw clay. His strangely shaped career, just shy of 50 years, is typified by intermittent periods of intense productivity. What has remained consistent is his unerring instinct for transforming the deadpan into the poetic.

Hawkesby’s career begins north of Auckland in the 1970s when he was introduced to the rudiments of studio pottery. From the earliest moment Hawkesby’s delight at working with clay was matched by a disinclination to adopt the then dominant Anglo/Oriental tradition of studio pottery. Like gorse and other species introduced to this county, this transplanted construct took on a greater veracity here than where it originated. Anglo-Orientalism soon morphed into a rustic homegrown ideal for re-imagining colonialist origins. Hawkesby recoiled at the widespread folksy bucolic pastoralism of the country potter selling their wares to urban day-trippers via a painted sign on the gate.

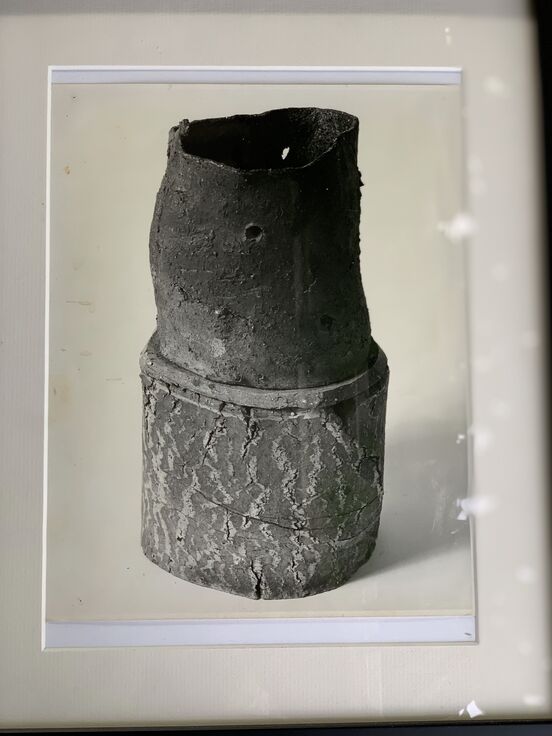

By 1977, the artist’s altogether different sensibility led him to return to Auckland in search of like-mindedness. The urban and urbane population of Auckland afforded broader conversations. In 1980, he exhibited five ceramic vessels he referred to as ‘incinerators’, as part of a group show called Five by Five, consisting of Warren Tippett, Bronwynne Cornish, John Parker and Denis O’Connor, at Denis Cohn Gallery, Auckland. Five works from five artists, all of whom were known to each other and all who had adapted radically different approaches in defiance of the prevailing orthodoxy. The Five by Five show, while briefly heralded as ‘new avant-garde ceramics’, was barely conspicuous in the cultural calendar of 1980. There were few in the audience at the time taking a professional interest and even fewer who would take much note. The exhibition became more celebrated as time passed, as the first local and substantial instance of post-modern ceramic practice.

Hawkesby is an individual who has never much cared for looking over his shoulder, preferring to establish his own context for what it means to make craft devoid of precedents or external prescription. Lived experience has always been more informative. The interval he resided in central Tokyo, from 1984 to 1994, was especially instructive and liberating for him. During this period, the artist was not particularly consumed by ceramics – although there was of course much to admire. He was more influenced by Tokyo nightlife and the elastic Japanese concept of shibui, an aesthetic of simple, subtle and unobtrusive ‘beauty’, found equally within live theatre, dress etiquette and the tea ceremony. Of particular consequence was the Japanese garden, designed to lower the heart rate during moments of slow respite and contemplation.

Hawkesby distills the aesthetic conditions of the garden and the tea ceremony in making works that are ideally situated on a table top. For art critic Peter Schjeldahl, the space between outstretched hands and the tip of one’s nose is an under-theorised zone in which the line between public and private is delineated. An intermediary zone in which eyesight gives way to the eccentricities of touch. This is the zone in which Hawkesby’s work performs and which he is determined to draw the viewer into. For him the domain of the table is inseparable from the primacy of the hand.

With a soft piece of clay in hand, it is easy to understand it as the ultimate ductile material. Each action leaves an indelible trace; material becomes indistinguishable from manipulation. The clay artefact is an event of its own materialisation, every physical compression, slightest indentation, crevice or fracture, is inhabited by its history. Hawkesby’s tangible pleasure in slapping, squidging, crimping, creasing and perforating raw clay is edifying. He offers an exquisite contemplation of the affordances of his medium. In addition to its plastic qualities, clay is plentiful and durable. It is thought that one third of the planet’s material mass is clay sedimentation and the rise and fall of civilisations may be measured in terms of the role the clay pipe had in bringing clean fluids and taking dirty ones away.

Hawkesby’s works are to be ‘visually felt’. The eye is the organ delivering that haptic experience. The gaze is compelled to move around the work, repeatedly arriving and departing across surfaces, volumes and intervening spaces, taking on board a succession of glimpses like a slow-motion animation. The work demands to be seen in the round. It engages the mobility of the eye and its aptitude to retain earlier visual impressions while being imprinted with new ones. In this manner the works resist being photographed. They are restless and serene at once and only through the passage of time can they be understood in their entirety.

Preoccupied with the palpable sense of intimacy, Hawkesby cultivates multiple centres of interest through a visual itinerary that diverts the singular point of view. With close scrutiny, we are able to feel the silky suppleness of an unglazed porcelain loop or the grainy matted texture of a blistered brick. The eye becomes squeezed in and between the fissures, feeling the sharpness of the crack and sensing the teetering of one form as it gingerly touches another. As it traverses the contours, the eye becomes quickened by the shiny slipperiness of a glaze and slowed by the implacable weight of a thick slab. Pleased or deceived, the eye has re-enacted an obstacle course and, in so doing, translates in purely abstract terms a bodily experience that performs that internal or ‘felt’ image of the body.

Central to the artist’s practice is a method of post-kiln assemblage. This format allows him to compose with pieces brought together from multiple firings that have occurred over substantial periods of time. Once selected, assembled and edited, this accumulation of components can be subjected to continuous making and unmaking. This approach is for Hawkesby a satisfactory and enjoyable way of working. It affords repeated revisions, akin to the rhythms of manual repair and unseen domestic toil – re-organising things, primping, puckering and gussying up, so all is orderly and presentable.

Hawkesby’s preferred method of firing is the rudimentary technology of a small, soda-fired, gas-burning kiln. The variety and fertility of various kiln environments can be as erratic as the weather in New Zealand. While a firing crack from the kiln is more usually the harbinger of despair, for Hawkesby it may be the occasion for a gratifying moment, carefully consumed and put to use. The range and variety of tick motifs within this exhibition attest to the artist’s profligate enthusiasm. These works are adroit, declaring an appreciation of the ooze factor and pleasure in decisive manipulation.

The genesis of the tick extends back in Hawkesby’s oeuvre to the late 1970s when it emerged as a response to an overabundance of the deeply encumbered cross in local art. Hawkesby’s tick has morphed into a signature calligraphic gesture, exemplifying the deft fluency with drawing in three dimensions that is the foundation of the artist’s diverse and rich visual syntax.

Another familiar form he revisits in Tender Brick is the incinerator. Early in Hawkesby’s career, an inclination for all things vernacular directed him to the 44-gallon drum, an incendiary device once common in back yards. This rusty receptacle for cremating household and garden waste was typically located at the furthest corner, out of sight and away from the fruit tree and washing line. During daylight hours it doubled as a target for DIY bow and arrows and as an uncommonly large cricket wicket. In the evenings it was a gathering place for kids eager to extend bedtime, and for men to avoid the kitchen, congregate, drink beer and poke a stick at the fire. Incinerators are now very rare, as are the large urban backyards that housed them.

A residual sense of the cylinder remains in Hawkesby’s work, but his latest incinerators are pried open as convex and concave forms which are stacked with precise irregularity, unfurling further opportunities for surface decoration. Exposing the interior confuses the condition of a ‘vessel’, where interiority is mostly to be assumed. Erosion at the border between interior and exterior can be considered the divining line between public and the private, joyful and ominous, intimate and incompatible. These are irremediable tensions, like joining a congregation of saints and sinners and not knowing whether you are being cuddled or accosted.

In making these incinerators perform, Hawkesby commands the play function of the decorative. Surface decoration and ‘form’ strive to be read in the same instance. Eyes tango between dark on light

and light on dark, dining out on the way the figure and ground swap places. These basic pattern-making principles arouse that bit of our DNA which celebrates the rhythm of pattern and exercises our visual pleasure.

The incinerators can equally be seen as totemic, reliquaries of past events, now incomprehensible in relation to any circumstances we might recognise. The seemingly random is implicated in ritual. Random being the sense of a calculating nonchalance. Ritual in the sense that these assemblages beguile with the ancient rites as practised by unknown peoples – hypnotic dancing in praise of a large pink wedge. The more we look to understand these assemblages the more we become implicated in imagining reasons for their inexplicable origins.

The artist does not work with preconceptions about what the work should represent. Hawkesby induces an aura of intentionality, ordained with unknowable purpose and where no obvious interpretation is readily available. He is viscerally occupied with how the work should look – harried and congested in a downtown fracas or in a cool and salubrious swoon under a pōhutukawa in summer. The works assume

a double identity, suggestive of a range of human postures and accessories – protective cloaks, halos and tendrils, rings and half hoops, tumescent appendages and droopy ones – while also emphatically retaining the real meaning of their origins as lumps, coils, knobs, wedges and slabs of vitrified clay.

Hawkesby also imbues his work with a sense of occasion. His role as master of ceremonies is well rehearsed. He bestows upon his pots what he bestowed upon his patrons during his two decades as gracious host and convivial proprietor of Auckland’s legendary café Alleluya. Politely forgoing established orders of merit in ceramics, Hawkesby’s opus in clay embodies an individual’s quest for unabashed elegance.

The exhibition’s title salutes Gertrude Stein’s 1914 publication, Tender Buttons, a work considered a triumph of unorthodox modernist experiment and decried as pretentious posturing. Stein’s insistence on the primacy of looking, unencumbered by preconceptions of language, is consistent with Hawkesby’s assertion of the incomparability of touch – and his cultivation of a private world where intimacy is understood and transmitted.

The artist’s bonsai monuments to human imperfection celebrate aesthetic experience. Hawkesby is nothing but formal, but his formality is always askew. He abstains from the overcast righteousness of the aesthetically pure and placid, and gladly embraces lopsidedness. Whether deflated or perky, Hawkesby’s forms exhibit the wear and tear of their making and retain a candid ‘offhandedness’, a sense of humour and insolence, as well as a desire to be sincere and beautiful.

It is now more than a hundred years since the Arts and Crafts movement spluttered and coughed its opposition to the dehumanising effects of the mass-produced, taking refuge within the civilising (and exclusive) endeavours of the handmade. Nowadays it is easy to regard the newest model of car or smartphone as sexy. We project onto objects human needs and wishes – an act encompassing both security and self-fulfilment.

Increasingly our material lives are prefabricated, preordained, and pre-packaged, denying us lived experience with materials ‘in the rough’. We are routinely divesting consumer items of their plastic packaging. We wrangle, rip and gouge at this unyielding material with obligatory derision about plastic in our lives and the lack of dexterity in our hands (or the product designer’s). In 1965, Anni Albers wrote of the debilitating and diminishing lack of material intelligence creating a deficit in people’s social and intellectual lives: ‘...we merely toast the bread. No need to get our hands into the dough. No need – alas, also little chance – to handle materials, to test their consistency, their density, their lightness, their smoothness.’ Manual dexterity has been reduced to keyboard skills and knowledge materialised through the acidic glare of a screen.

There are two great attributes to Hawkesby’s practice. A deep attachment to and learned appreciation of clay’s materiality with the will to extend the medium as a means of individual expression. Hawkesby has an ability to simultaneously court the ritual and the casual, where preciousness and serendipity comfortably coalesce. No matter whether we catch these clay objects in an act of loitering or levitating, we find a material equivalent for what could be described as the ‘livedness’ of the body – a recognition within our nervous system that these objects, at their most profound, talk to our corporeal reality as sentient beings.

Albers, A. (1965). Tactile Sensibility. In T. Harrod (Ed.), Craft: Documents of Contemporary Art (pp.27-30). London: Whitechapel and MIT Press

--

Peter Hawkesby was born in 1950, Cockle Bay, Auckland. He began making pottery in 1974. It wasn’t until his return to Auckland in 1977 did he find a conducive environment for developing his distinctive practice. From 1984, Hawkesby lived in Tokyo. Upon returning to Auckland in 1994 he spent two decades as proprietor of the iconic café, Alleluja in St Kevin’s Arcade. In 2016 Hawkesby resumed working fuIl-time in ceramics.

His work is represented in public and private collections throughout New Zealand, including The Dowse Art Museum, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Hawkesby’s exhibition history includes Five by Five, Denis Cohn Gallery, 1980, Auckland; Auckland Studio Potters Annual exhibition, guest exhibitor, Peter Hawkesby, Auckland War Memorial Museum, 1980; Dirty Ceramics, The Dowse, curated by Sian Van Dyk, The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, 2019 and Professor Tick & Company, McLeavey Gallery, Wellington, 2020.

Richard Fahey is a senior lecturer in Design and Contemporary Arts at Unitec, Auckland. His research activity is focused on material culture of Aotearoa. As an independent writer, critic and advocate, he addresses contemporary cultural production and its reception via the historical and institutional contexts of education, critical discourse, collection and exhibition. His research takes the forms of writing, curating and participation in the visual arts sector as a teacher, speaker, assessor and critic.

Peter Hawkesby, Cook Strait Te Moana-o-Raukawa, 2020. Photographer: Samuel Hartnett

Peter Hawkesby, Incinerator, Five by Five exhibition, 1980. Denis Cohn Gallery, Auckland.