-

Author

Kathy Waghorn -

Date

6 Apr 2024

Essay

I was moving too fast to see

Beyond the fat oak trunks, a low-slung, rectangular wall lies close to the ground’s surface. Punctured with small white-trimmed windows, adorned with plumbing pipework, the brown brick shows traces of faded graffiti.

I’ve come to this building from its rear, the side that backs into the gardens, where, clustered in groups on the grass, with bikes and dogs, picnickers make the most of the after-work sun. Around to the side, a eucalypt trunk presses close to a tall window. With decorative fins that double as security bars, the whole geometric assembly is Sol LeWitt-like; shifts in the uniform brick profile generate a subtle decorative feature. As I move round towards the street, the front is revealed, all glass, windows and sliding doors. Above the entrance is a woman’s name in a chunky type, all in caps: EMELY BAKER.

Located on a prominent corner in Fitzroy North, Naarm Melbourne, the Emely Baker Centre sits within the northern perimeter of Edinburgh Gardens. Though situated in plain sight, the building strangely evades notice, a shadow of its namesake who has all but disappeared from the public record. A shoulderhigh wall faces the street, forming an enclosed courtyard to the glazed front-side; a varnished timber soffit

offers a small texture change from the relentless brick; and fixed to the western wall, a hip-height metal cage encloses some kind of utility connection and offers a shelf for an abandoned bottle of beer. Designed in 1971 in the ‘International Style’ by K. Murray Forster and Walsh Architects, this now empty building has seen little use since it ceased operation as a child and maternal health centre in 2008. Located on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, the building and its landscape are both an example of, and embedded within the broader history of the deliberate, continual and insidious erasure of Indigenous and ecological life, typical of settler-colonial urban projects.

Paintings and maps record the pre-colonial environment: an area with billabongs, scattered trees and a small creek, surrounded by open grassy plains and abundant wildlife. Set aside as a public reserve in 1859, Edinburgh Gardens, in both name and form, are a powerful symbol of colonial order and of the nature and health philosophies inextricably linked to the project of colonisation. Overlaid with formal and regulated paths, delineated garden beds with imported European plants and trees, regulation sports fields and lawn areas, drained and filled wetlands and a diverted, buried and plumbed creek, the gardens amply illustrate the problematic aesthetics of the picturesque that ecological writer Geoff Park has noted as a complex attribute of colonisation.1

Over the years, different buildings, water storage facilities, fountains, paths and bridges have been erected and removed from the gardens. Historic maps record that a large and elaborate fountain once stood directly behind the Emely Baker Centre on the path I took to reach it, yet no sign remains – all traces of past structures, past inhabitants or natural ecologies are smoothly covered over. Far from being neutral or static, the Emely Baker Centre and its context are continually evolving. After 10 years of dormancy, the building tentatively reopened in 2018 as a venue, available for hire via a convoluted bureaucratic system. This disheartening repurposing epitomises the “normalising authority of neoliberalism”2 that sees community buildings as just another blank space to be occupied for a fee; the public can now make a booking at the precise rate of $69 per hour. However, given the centre’s current state of neglect and under-use, it seems that Emely Baker may be the next entity to leave the gardens without trace.

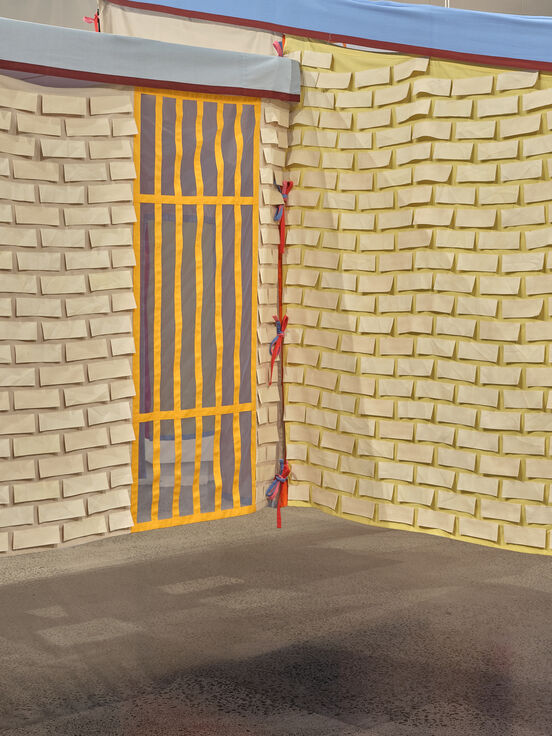

What to make then, of this new Emely Baker, visiting Tāmaki Makaurau in a gorgeous billowing dress? Who or what are they, and how did they get here? Moving gently in the late summer breeze, this Emely is not a mirror, twin or double of the Naarm building, but instead a herald of future possibility. Taking the form of a sectional model at 1:2 scale, with the section-cut mapping the original construction drawings, this Emely is a series of surfaces. The three-dimensional heft of brick is compiled as 2500 separate fabric pieces, 48 panels of linen and myriad appliquéd layers of cotton and thread. Collaborating with a professional tent maker, a sewer and an industrial designer, Esther Stewart has translated Naarm’s Emely Baker Centre into a levitating hybrid tent-garment. Far more precise than a blanket cubby house, and released from the earthly qualities of brick, jewel-coloured panels here pick out door trims and sills, traced from elevation drawings through layers of baby-blue cotton linen against lemon, mustard and brown.

For Esther Stewart there is clearly pleasure in connecting with fabricators and appreciating their knowledge as the seed of an idea expands through collaboration. Stewart is aware of the raw materials she’s using – their politics, sites of production and labour practices, part of a global flow of trade mostly hidden in centres of consumption like Naarm and Tāmaki – and this Emely Baker is a modularised construction, made within the constraints of material optimisation and minimising waste. Stewart attended carefully to the architectural drawings in creating this new Emely, while making the transformation through the language of fabric construction – tabs, casings and plackets. Described in this language, each panel, delineated by the width of the fabric bolt, is cut, sewn, labelled and indexed, then carefully packaged as a kit of parts for relocation. Installing Emely here in Objectspace must have been a little like setting up the tent for a family holiday, hopefully following the instructions so that Tab A meets Tab B in just the right position, all the while projecting the potential of a summery inhabitation. Expanding on the use of metaphors of materiality and fabrication in writings about the relation between text and image, Sarah Treadwell has noted the “deployment of fabric, and its actions”. Fabric might be used to pursue understandings of the relationship between text and image because of its elasticity, “its associations with production or/and its potential for transformative moves” 3. It is exactly this transformative potential that Esther Stewart invokes with this new Emely.

This Emely Baker is both a propositional sketch and a project of advocacy. Demonstrating an appreciation of practical problem-solving as part of a double-stranded practice that moves across sociocultural-ecological research and hands-on making, Stewart’s translation demonstrates the potential of building rehabilitation. The artist’s engagement with this currently under-utilised building offers an opportunity for an in-depth reassessment of the specific building and site, but also of contemporary building practices more broadly. The adaptive reuse of buildings is familiar to us. However, the retention of ‘heritage’ in building can be problematic in perpetuating and enshrining legacies of colonial power structures. This Emely Baker, cut from cloth and holding the potential to be reassembled in different configurations, mobilised as smaller or larger entities, offers a model of ‘adaptive reuse’ that operates as both a critique of those power structures and a speculative reinvigoration of potential use.

This adaptive reuse is akin to that of Lacaton & Vassal, French architects who have inspired new thinking about the merits of ageing modernist social housing. In an era of critical attention to embodied carbon, they say: Don’t demolish. Instead, relish in the joy of reuse. Internationally acclaimed for their efforts to keep existing buildings whenever possible, no matter how unpromising or unloved – as outlined in their famous PLUS manifesto – Lacaton & Vassal put these ideas into practice through adding an additional layer to 1960s and 70s tower housing. Drawing from stocks of materials used in agricultural buildings, such as corrugated steel and polycarbonate, this new layer, ‘clipped’ to the façade, offers larger openings and produces climate-mediating (shady in summer, sunny in winter), spatially generous intermediate spaces between interior and exterior. These ‘free zones’ are open to occupancy in a myriad of ways. Looking through the rich photographic documentation of these finished, occupied projects, I’m struck by the temporal qualities of the in-between zones, and the recurring use of mobile fabrics in curtains, mats, shade sails and blinds that line and pad the spaces. In one photo there is even a tent erected in the deep veranda.

Can’t you just imagine a dry building report commissioned by Yarra City Council forecasting a bleak future for the Emely Baker Centre in Edinburgh Gardens, Naarm? The new Emely Baker, here at Objectspace, made from carefully sourced materials, drawing on local fabrication knowledge and generous exchanges of labour, suggests other ways to operate. Like a protest banner, this is a project held up high: demanding more imaginative thinking about the future of ageing community buildings, advocating for the retention of built fabrics, and revealing and questioning the bio-political techniques that are normalised through architecture everywhere across our cities.

—

Esther Stewart lives and works in Naarm Melbourne, Australia. She creates paintings and installations that call on visual languages and concepts from architecture, design and geometry. Recently, Stewart has collaborated with architects and craftspeople to extend the spatial and material possibilities within her practice. She completed a Bachelor with First Class Honours at the Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne in 2010, where she has lectured in the School of Sculpture and Spatial Practice, and completed a Masters of Architecture in 2023. Stewart’s work is held in public and private collections internationally and she has worked on major commissions for Bendigo Hospital, SlowBeam, ChenChow Little, Shepparton Art and for the Crowsnest Metro City train station in Sydney. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at galleries and art fairs, including recently in Melbourne Now at the National Gallery of Victoria and in The National 4: Australian Art Now at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Hailing from Ōmata, Taranaki, Kathy Waghorn is co-director of HOOPLA, a Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland based ‘ultra-local’ practice carrying out urban research for place advocacy. HOOPLA are engaged with how people know, use and value places, and how places can be re-imagined and re-purposed. Alongside this work, Kathy develops exhibition projects that investigate contemporary architectural practice, making opportunities for wide public engagement with issues in the built environment. In 2016 Kathy was Associate Creative Director of Future Islands, the New Zealand Pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale and in 2019 she curated the project and book Making Ways: Alternative Architectural Practice in Aotearoa at Objectspace. Kathy’s research, teaching and practice work has been recognised through awards including the 2023 Architecture + Women New Zealand Munro Award for diversity in architectural practice. Kathy has taught at the University of Auckland and AUT. She is an Associate Professor and acting Head of Architecture at Monash University, Naarm Melbourne, and a member of the Monash Urban Lab.

—

Footnotes:

1. Geoff Park, ‘The Ecology of the Visit’, Reading Room: A Journal of Art and Culture, issue 07, 2015, pp 96–109.

2. Amelia Winata, curator of the exhibition Wayfind, a Next Wave x West Space Co-commission, held in the Emely Baker Centre, 6–20 May 2018.

3. Sarah Treadwell, ‘Writing/Drawing: Negotiating the Perils and Pleasures of Interiority’, IDEA Journal, vol 12, no 1, 2012,

p 3, https://journal.idea-edu.com/index.php/home/article/view/89/52

Esther Stewart, I was moving too fast to see, 2024. Photographs by Samuel Hartnett.

Esther Stewart, I was moving too fast to see, 2024, 16 Mar–19 May 2024 at Objectspace, photograph by Sam Hartnett

Interior of The Emely Baker Centre, photograph by Emily Weaving

Exterior of The Emely Baker Centre, photograph by Emily Weaving

Exterior of The Emely Baker Centre, photograph by Emily Weaving

Exterior of The Emely Baker Centre, photograph by Emily Weaving