-

Author

Madeleine Chapman -

Date

27 Apr 2021

Essay

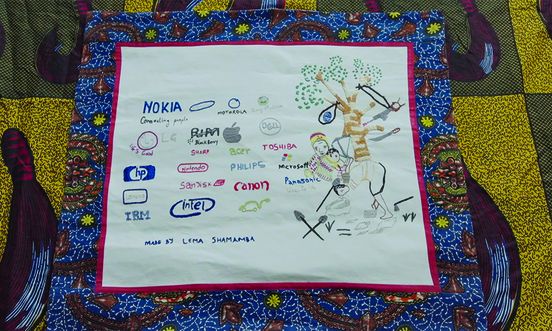

The Single Object: The Incredible Life Story Behind This Embroidery

Every stitch of Lema Shamamba’s embroidery tells a part of her story – and brings her closer to her homeland.

CW: Violence, sexual assault

"I didn't have an option," she says. If she didn't leave, she would be killed.

Lema is calm when she recounts all it took for her and her family to be living in West Auckland in 2021. Born and raised in Bweremana, a district of Masisi in the eastern territory of the conflict-plagued DRC, Lema grew up watching her small, community-focused village become an attractive target for large multinational companies. The companies weren't interested in Lema, her neighbours, or even the village itself. They wanted what was beneath them: coltan.

Short for columbite tantalites, coltan is a metallic ore from which tantalite can be extracted. Tantalite is used in the manufacturing of almost every electronic device. The grounds of eastern Congo are rich with coltan.

With a history already riddled with conflict, coups and human rights abuses, the mining of coltan displaced thousands of Lema's neighbours. "Those companies, they go there to take those minerals. When they come with the guns, you don't have any option. You will be moved. When they take this, they just destroy our community… Raping women, killing children, killing your husband in front of you."

Lema's husband was killed during the conflict, after which she made the uncommon decision to go to university. "Always I saw in my village, women were very… I don't know, women had no value. I just wanted to know about more culture and learn about people." While at university, Lema began protesting the killing of indigenous people, including signing a memo to the governor at the time. When word got out that militia were looking for those who'd signed the memo, Lema grabbed her youngest child and fled.

Lema has always known how to embroider. It was a skill she learned in her village as a child, along with how to work the land, growing fruit and vegetables. When she left the DRC, she and Pasifique lived in a refugee camp in Uganda, with little more than a sheet over their heads, before fleeing again to the capital city of Kampala, where they lived on the street, under a mango tree, for two years. "No toilet, no nothing. If it's raining, I'm there. If it's the sun, I'm there."

During the day, Lema would walk the streets. "When you are homeless you just go up and down, up and down." She frequently visited the local police station, hoping for any word on her family back home. On one of these walks, she saw two children who looked familiar. They were hers. "It was a miracle," she says. She hadn't seen them in three years.

Lema and her family got a chance to escape when a journalist from the national newspaper interviewed her for a story on homeless refugees. Her interview caught the attention of the local UN office, and in 2009 Lema was granted an interview to leave the country. She spoke to a woman on Wednesday and on Friday was on a plane to New Zealand with her three children. She had no idea what or where New Zealand was, but anywhere was better than the base of a tree.

On arriving in Auckland the family spent six weeks at the refugee settlement camp in Māngere, before moving to Rānui. They came with nothing. "When you leave, you don't think about material things, only your life." In Rānui, Lema connected with other refugees in the community and joined the Rānui Action Project, helping to lessen the oft-experienced isolation of refugee families. She offered her expertise to the Rānui community garden, where rows of lettuce, potatoes, and any number of other fruits and vegetables are nurtured by "Mama Lema".

Then there's the embroidery. After having little opportunity to embroider in Uganda, Lema picked it up again in New Zealand, making decorations for her home and small trinkets to sell at the markets. But soon she felt an urge to use it for something greater. "For Congo, the story we told just in craft. Because all people in my country don't know if they are artists, but I can say the whole village is like artist people. It's about telling a story through the thing you made."

The stories Lema now tells through her embroidery involve guns and blood and severed limbs, crying babies and weeping mothers. All stitched delicately alongside the immediately recognisable logos of the world's largest tech companies. "In those logos, they have responsibility," she says.

The message is clear in all her work – it's a message of cruel reality, and the cognitive dissonance of millions of people who enjoy the advancements of modern technology while ignoring the suffering and death involved in making them. But it's also a message of hope, that by sharing ugly truths in a beautiful medium, every person who witnesses Lema's embroidery will be compelled to do something, anything, to help.

"My purpose of all I do, is to let people know the story of my country and the people who live in it," says Lema. "I'm still missing my people, I'm still missing my culture. I can say when I'm doing my embroidery, I'm not in New Zealand. My body is physically in [New Zealand], but my mind is in the Congo."

Every day Lema tells her story and the story of her country, one stitch at a time. And each stitch brings her closer to home.

This content was created in partnership with The Spinoff.

--

Madeleine Chapman is the co-author of Steven Adams' bestselling autobiography; Steven Adams: My Life, My Fight (Penguin Random House NZ) and a staff writer at The Spinoff. She was named the 2018 Young Business Journalist of the Year. The Single Object was directed by Madeleine Chapman and Piata Gardiner-Hoskins and produced by Hex Work Productions for The Spinoff in association with Objectspace.

Need help?

Phone support:

0800 88 33 00 National Rape Crisis helpline. Find helplines and websites for those affected by sexual violence in your own area at rapecrisis.org.nz

0800 623 1700 HELP Auckland – free from any phone, 24 hours a day, every day

0800 733 843 Women's Refuge crisis line — free from any phone, 24 hours a day, every day.

0508 744 633 Shine Helpline — free from any phone, 9am to 11pm every day.

0800 456 450 It's Not OK info line — free from any phone, 9am to 11pm every day.

Online support:

You can ask for help online through the Women's Refuge Shielded Site service available on popular New Zealand websites.

The service is private and won't show up in your browser history, so you can get help without anyone finding out.

1. Go to a New Zealand business website that offers the service, such as The Warehouse, Countdown and Trade Me.

2. Click on the Shielded Site logo, usually at the bottom of the website.

3. You can ask the Women's Refuge for help, make a plan to leave and learn how to stay safe online.

Lema Shamamba. Photo: The Single Object.

Lema Shamamba's embroidery. Photo: The Single Object.